What Exactly is a Mosque?

Ask most Muslims, or come to that anyone in the street, what their idea of a mosque is, and you will get a mixture of opinions; but most of all you will hear – “a dome and a minaret and probably something old.” It’s not something people think about very much,

The very first mosque in Medina was as far as we know just a piece of ground, set aside, clean, with probably a low wall to keep out animals and originally oriented to Jerusalem before it was changed to Mecca 17 months after the Prophet’s arrival in Medina from Mecca. It may have had some reed covering as sun protection. And a famous tree. A place to safely put your head on the ground.

When I was asked to come up with a quick sketch design for the Cambridge mosque in late 2008 (see previous post) to help raise funds for the land purchase, the brief asked for a mosque in Anglo-Ottoman style for 1000 worshippers, 80 cars and to be costed and to be completed in three weeks. A bit of a tall order as it was many years past that I had designed any building. But is an architectural style all that a mosque is about? Surely not. A mosque I visited in a shanty town in Meknes, Morocco, in the 1970s, known as the Burj, consisted mostly of corrugated iron with an earth floor and it was much loved by the local inhabitants. But for now let’s enter the world of style and see where it takes us. So Anglo-Ottoman. What does this suggest?

The Ottoman style is pretty straightforward with striped brick courses, courtyards, symmetricality, flattened domes and pointy minarets, marble and stone. But Anglo? Would this be Gothic, Tudor, Classical, Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, Modern?After some consideration I decided that because of the eclectic nature of Victorian architecture, there could be a possible fusion of some Victorian design with such Ottoman architectural ideas. This would seize on the Paxton glass and cast iron constructions that can be found in Kew Gardens, London and of course his famous cast iron dome in Buxton, Derbyshire. Include the Crystal Palace which burnt to the ground in 1936. Paxton’s work was for me by far the most honest and elegant of Victorian architectural constructions, and I felt there was a possibility of marrying it somehow with the modesty and intimacy of buildings like Rumi’s tomb in Konya with its simple volumes of domes, cones and minarets. I hadn’t considered, and was not asked, to come up with an ecologically sustainable building.

The Catholic Cathedral, Victoria Street, London

Interestingly John Francis Bentley’s Catholic cathedral in Victoria street, London which opened in 1903 was probably the first attempt to mimic Ottoman ideas in an English city setting. Inspired by the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and holding 3000 worshippers it is an explosion of striped brick work and towers and domes. I never found it that attractive in the past but its Byzantine and Ottoman influence now makes it a building of interest.

After the Cambridge Mosque competition winner was announced — the Marks Barfield partnership, the designers of the London Eye — my first reaction was disappointment. Did this imply that those who promoted the competition wanted a kind of fun-palace with a minaret helter-skelter from which, after calling the prayer, the muezzin would rapidly descend and then launch himself into the mosque. Obviously not, but it did occur to me.

I’m writing this prior to visiting the mosque itself and I will give my reactions later in this post. Although this visit was to be to the opening in December 2019, I’ve taken over three years since the opening to figure out quite what to write. I realized in advance that a kind of conventional architectural critique might not apply in this case. As we are entering a kind of post post-modern era of almost universal social upheaval and anxiety as well as what looks increasingly like an environmental endgame and technological Armageddon then we can maybe throw away some of the architectural rule books for now. Does it really matter anymore?

Herein is the core problem: Architects. They cause a lot of problems. More often than not, the topdown freemasonic idea of the architect as God — the all seeing eye on top of the pyramid guiding every fragment of the design from roof spans to doorknobs — is where it all goes wrong in my opinion. But it’s almost impossible now to return to an age of entirely craftsmen-built structures: i.e. the many early Gothic and Romanesque buildings that we know and love. It’s virtually impossible in the current financial, commercial, legal and construction environment like contemporary Cambridge. The fund-raising design I came up with (see previous post) would have to have had some frightful compromises to get built. The dome would have to have to have been fake and the stone work just facing on concrete block walls. Very unauthentic. The shape and interior might have been more pleasing and mosque-like but that’s about it.

Style seems more and more to be about the theatrical flavour of the building like some kind of stage set. You want Ottoman? No problem. The Turks will build you a mini Sultan Ahmed with immaculate interior tiling and mihrabs. Anywhere in the world. Or compromises like the Park Rd mosque in London which was once portrayed as a public library with an onion on the top. The late Martin Lings told me that a beautiful Tunisian scheme was due to be submitted for the Park Rd mosque competition in the mid 1970s, but mysteriously disappeared the day of the competition.

If you are looking for elegance in style then the Paris central mosque is hard to beat, the way it takes up a whole city block and was conceived as a complete social hub with hamam, restaurant, library, madrassah, book shop etc. around courtyards in true Andalusian style inspired by the Qarawiyyin mosque in Fes, Morocco and Tunisian Andalusi architectural motifs. Very much to do with France’s colonial activities in North Africa. The Woking Mosque, the first custom built mosque in the UK is essentially a Mogul style mosque, another ‘style’ to add to our list.

To also suggest that ordinary folk could assist in the building in a small way in the construction of a mosque is met by raised eyebrows and the red flag of ‘Health and Safety’. But this is precisely how many mosques have traditionally been built down the centuries. Many of the workers who built the Faisal extension to the Prophet’s mosque in Medina in 1943 were volunteers not wearing hard hats, working with minimal machinery and carrying materials up ladders. And over the time of its construction there were no fatalities. They also spoke of what was an uplifting experience for all who volunteered. Building a mosque could and should be an act of worship if possible. But virtually impossible in 21st century UK. So what is the elusive quality that makes for a great mosque or any place of worship? Does architectural style come into it?

I’ve had to deal with a few mosque designs myself over the last 35 years, and none of them were that successful for many reasons. So I have a slightly jaundiced view of the subject. Crafts of Islamic origin in the western world are all alive and well with burgeoning calligraphy schools and geometry seminars and the growth of specialists in islimi, ebru, geometric woodwork and zillij etc. But architecture remains a centrally challenging problem. This is because a mosque design brings together the difficult conjunction of mosque committees, planning and building law, local politics, public opinion, fund raising, before you even get near the actual design of the building and its construction and most problematic of all: what style?

I have a simple litmus test. When you walk into a mosque (or come to that, any building) you are greeted by the overwhelming intention that’s behind the establishment of the building. Its spirit, in other words. I’ve walked into many mosques and on the whole you are welcomed at the door by all the generosity and hard work and the love that went it to its creation. This is what matters. The donations, the struggle, the legalities, the local objections and so on and in the case of old mosques in Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Turkey, centuries of devotion as well. Light upon Light. There’s no time that it wasn’t a challenge to get people to cooperate enough to erect a building for the glory of God. But cooperate they did. It’s that commitment, chemistry and pure faith that greets you as you enter such buildings.

The Cambridge Mosque

Aside from the design of the building itself, what has most impressed me about the new Cambridge mosque was the trouble taken to consult the future neighbours and local authorities even to the degree of the appointment of a local non-Muslim resident to the competition jury. Not the style or lack of style. Also careful consultation with the future women worshippers in the mosque on their requirements. This indicated the kind of care taken and this is what you meet when you first enter the building. This wasn’t like some UK mosques built in the 1970s which were built with a kind of fortress siege mentality, not through any fault of their own but just because they knew no different.

Leaving these fundamentals aside for now, what did the architectural establishment and the building industry make of the new Cambridge Mosque? It scored well on many counts, garnering quite a few awards. But it’s praise has been more for its eco credentials and zero carbon technology than traditional architectural attributes—e.g.. siting, proportions, aesthetics, planning, detailing, architectural influences etc. In that sense it’s hard to categorise. This is a technological age, like it or not, and what impresses is primarily the functionality and the technology of the building discretely at work behind the scenes like the solar panels the recycled grey water and the heat pumps in the basement. Presumably employing technology in an attempt to help undo the damage done by …… technology.

Although an eco mosque is a welcome idea, it’s not for me the most important cake in the larder. Is it a place you want to pray in? Is it well kept and secure? Can you find solace and tranquility in it to calm a fevered brow? Does it have to reflect history and the local vernacular? Is it a place where I can get help if needed? I suspect most worshippers have their own idea of what a mosque should be but if it is clean, and uncluttered and built with some love it’s hard to go wrong. Witness all the old churches, synagogues and cinemas in the UK converted into wonderful mosques. I understand the Muslims of Cambridge were offered one unused church as a mosque but only on condition the statuary was left intact!

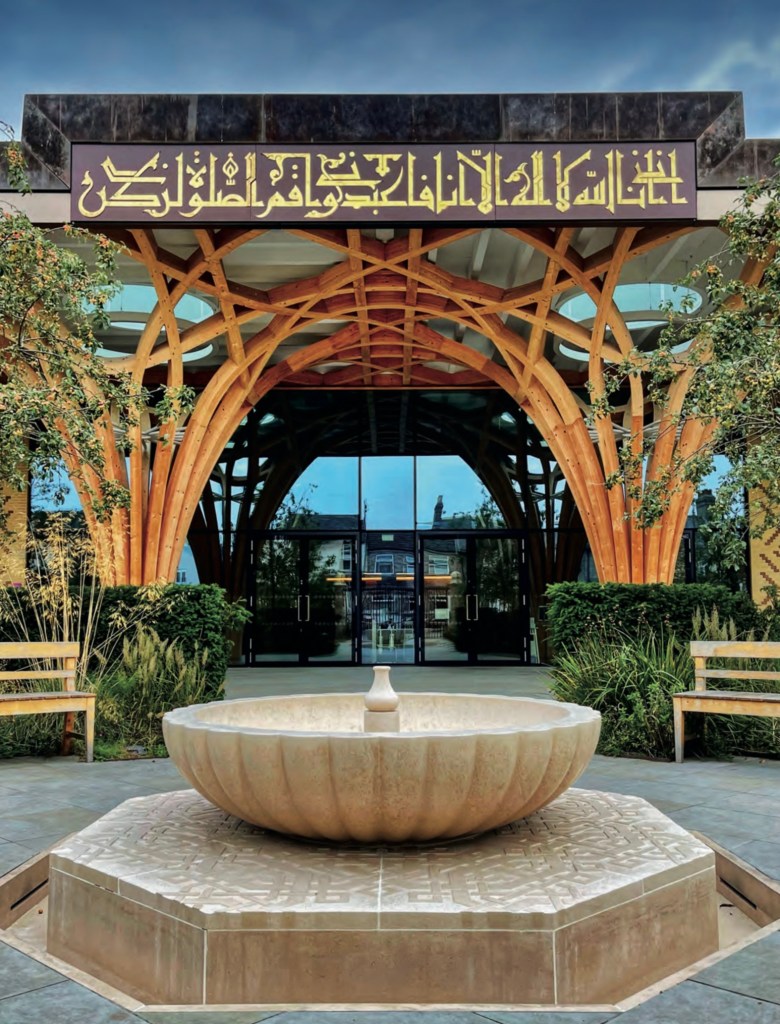

There are certain well considered functional aspects of the Cambridge mosque worth mentioning. Clearly because of the street congestion and overcrowding at the nearby previous Mawson Road Mosque the underground car park and frontal garden spaces facing on to Mill Rd were crucial. Being set back from the road was also essential. The frontal garden and atrium clearly were a good idea to allow for the decanting of a lot of people on Fridays after the main weekly prayer. Also because of the inclement British weather, the covered area or atrium immediately outside the prayer hall is an indispensable space in which people can meet and also gain access to the other areas of the building. This might seem obvious but these matters need forethought.

The golden dome of the mosque does seems a bit odd quite honestly, as if it was an afterthought. Domes were originally built as a way of creating a large uninterrupted space but constructing them traditionally required great skill. On the other hand in this case the dome does create a focal point within the prayer space. It’s symbolic. Without these features we would just have a shoe box which could be mistaken for a telephone exchange or a car showroom, so these features serve to distinguish it as a religious building and differentiate it from the surrounding structures. But it doesn’t stop it being odd in my book.

It’s not clear if the spruce tree columns and vaulting are structural i.e. holding the roof up – or not. I think they are not. (correction: they are) A heresy in some architects books. Actually I found out that they are an off-the-peg product by the Swiss manufacturer but specially adapted for the mosque design. To have constructed them in stone like the fan vaulting roofs of Kings College Chapel in Cambridge would have been impossibly expensive. So wood was obviously a simpler proposition. Maybe not so durable as stone. We shall see how it weathers.

I have reservations about modern building techniques as they are just a reflection of some of the ruthless commercial ways modern society functions. There’s little of craft left in the building process these days which has now become the assembly of a kit of machine-made parts specified by an architect and assembled on site. The under-structure of the new mosque, with its reinforced concrete columns, is still assembled in situ but only as a support for the prefabbed components above like the dome and the spruce trees. This mosque is a curious mix of traditionally laid brick walls, reinforced concrete columns and slabs and of course the trees. So there’s a hint of creating an ambience. Purist architects rile at this but for some reason it doesn’t bother me. It is light and youthful as a result and not weighed down with top heavy authoritarian traditionalist dogma.

There is not much evidence of the conscious influence of tradition here except for the geometrical marquetry doors, inspired by Keith Critchlow. The geometric floors were doubtless cut with lasers but that is the craft of the modern world we live in if you like. Lasercraft. It’s a craft but of this time. But the geometry is timeless and self evidently sacred. The same goes in a way for the wooden trees which echo, as I have said, the beautiful stone fan vaulting in the nearby Ely Cathedral and Kings College chapel.

I finally visited the mosque at its ceremonial opening in December 2019 and although the event had been hijacked by the Turkish sponsors as a kind of publicity platform for their head of state Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it was hardly surprising given how much they had contributed to the £23 million bill. Yusuf Islam is a patron of the project and his involvement was much valued in publicising it and in fundraising. He had personally invited the Turkish head of state to the opening of the mosque. It was a massive security operation with layers of identity checks and a huge police presence. A bit strange compared to the modest opening of the Paris mosque in 1926 with a prayer led by the famed Shaykh Al-Alawi of Mostaghanem.

Predictably some were disappointed and one attendee complained to me that he thought the new building was a mausoleum for crafts, which I took to mean he felt there was no real craftsmanship in the building. He also said he felt it had no baraka. Others disagreed. Most people I spoke to said they loved it. It’s somehow just very….Cambridge.

Tradition vs Traditionalism

In an interview in 1989, the Yale historian of Christianity Jaroslav Pelikan said: “Tradition is the living faith of the dead; traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. Tradition lives in conversation with the past, while remembering where we are and when we are and that it is we who have to decide. Traditionalism supposes that nothing should ever be done for the first time, so all that is needed to solve any problem is to arrive at the supposedly unanimous testimony of this homogenised tradition.

This quote highlights for me this collision of ideas about what is in this case, a mosque, and is supposed to be why to view the new Cambridge mosque through the lens of the traditional architectural critic is maybe a mistake. Most people are not architectural experts and if they understand enough to say they like it, who are we to carp? This hi tech, carefully thought out and well built building, right down to the the foot driers and potted plants in the ablution areas, is everything that the younger generation of Muslims and even non-Muslims might aspire to. If you want ‘traditional’ tradition there are many ancient mosques all over the world to visit and I more than anybody appreciate them.

Cambridge however, is a centre of the world of science and innovation (like it or not) where the atom was first split and DNA was first unveiled and is filled with people who will respond to the youthful spirit of this mosque. The building offers the answer to a multitude of needs to do with the prayerful and the pastoral as well as the social and physical needs of a community like weddings, funerals, local cultural events and so on. It is also important because of its dialogue from the outset with the surrounding community at a time when to avoid this is plain dangerous.

Download the latest Cambridge Mosque Brochure