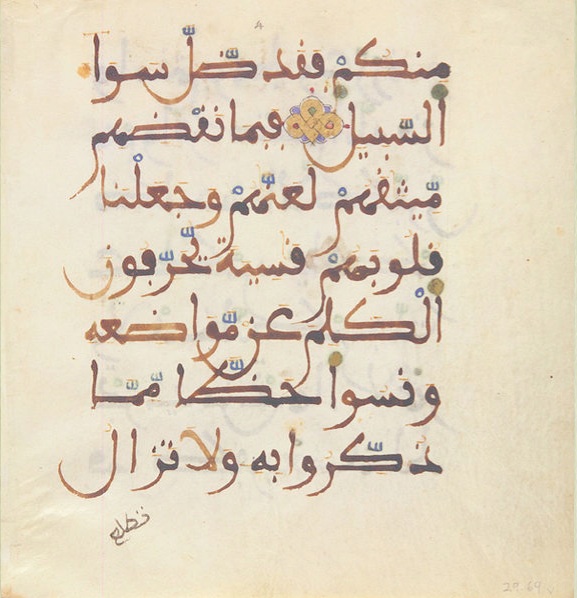

For years I have tried to understand what the maqams are (or maqamats, known as nawbas in Morocco) and I hope these few words here don’t confuse things further. In these posts I have always sought out subjects where the global homogenisation of culture is forcing out the subtler and more indigenous remains of previous traditions – things which enrich and complete the human experience whether language, calligraphy, art, architecture or music. A great loss to us all and future generations. This mode of music is one of the things being pushed out by rigid modes of western harmony. But first I want to step back a bit for a more general view of things.

Sacred Geometry

In my early years I was very conditioned against the concepts of sacred geometry by views instilled in us in the early 1970s. We were taught to view it as a kind of masonic Schuonian conspiracy. Since the drugged days of the 1960s when things like numerology were the rage, I have been a bit suspicious of mathematical explanations of the universe as the truth is that it left us all confused. Like the teachings of Gurdieff and Ouspensky, it was all redolent of higher realities but in fact left you amazed, but helpless, with no prescription of what to do.

A few years ago I saw a short lecture in Granada by John Martineau, publisher of Wooden Books, about sacred geometry and I revised a lot of my opinions on the subject. He expounded on the empirical geometry in creation from flower forms to shell formations and crystal structures – the undeniable geometry underpinning, well just about everything. A recent BBC TV series called The Code presented by Marcus du Sautoy also explored the mathematics of everything in existence as the key to understanding it. Whereas John Martineau suggested a new interest for me in divine mathematics, Marcus Sautoy left me quite uninspired with little understanding of it. The Code was a triumph of form over content with admittedly stunning computer graphic presentations but nothing that really moved me or got to the nub. What both Martineau and du Sautoy had in common was that they described well something fundamentally true except that they shied from talking about the root truth which is what I was looking for. In this, they share where modern science leaves us all short changed. Like the Hadron collider, the multi billion pound white elephant buried in the ground under the French Swiss border, it may unveil secrets about the stuff of what we perceive as solid matter but seems likely to leave us none the wiser about what it all really means. This vast subterranean tomb will deeply puzzle future archeologists whose only explanation will be that it was an underground 28 km greyhound race track.

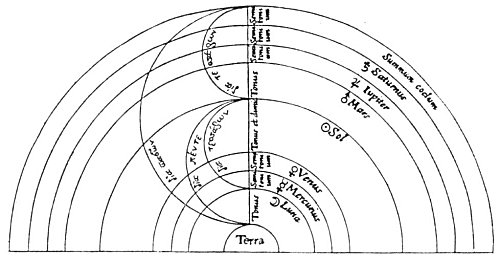

Such divinely ordained things as the Golden Section are remarkable in that they seem to underpin beautiful proportions in the natural world as well as man made creations in art and architecture. I only digress into geometry here to illustrate how I also perceive the musical maqams by analogy. Empirical geometry – empirical musical harmonies. The golden proportions of musical harmony. I have no proof for this but I have hunch that the maqams are what the Pythagorians called the music of the spheres. These are harmonic sequences which are empirical, in other words they are not man made. They have pre-existed everything and permeate all of the created universe which includes us.

Maqamats

Pythagoras connected the harmonic relationships of the earth and the celestial bodies with musical harmony and beauty and so should we with the maqamats. The origin of the maqamats is not known but my assessment is as follows. Most of us in western cultures understand the difference between the moods of major and minor keys. These are two modes which we are preconditioned to respond to. Minor – sad. Major – happy. Now imagine many more modes which we are capable of responding to involuntarily but which right now we are not familiar with. This is the clue. Given this we can enter into a new universe of musical experience. Not the arbitrary emotional and horizontal imaginal worlds of western musical composers but something truly celestial and in harmony with something greater than the human self and a form of worship in the right situation. This music is not one of sensuality but one of elevated and inspiring beauty. It is not some cold mathematical world either but one which unlocks the heart and its secrets. This understood, western music can still inspire and unlock incredible zones of emotional experience which can be beneficial but may not be very pleasant sometimes in its inner evocations, like the music of Wagner. But it can be a window into the world that produced that music and musically very moving. But it is not celestial music.

Music is for some a difficult territory. For reasons of culture and religious legal opinions, some people have forbidden it to themselves and their communities. I have never visited India or Pakistan but I know that some sublime music has come from the subcontinent and this aversion to music appears to be something that lives mostly in expatriate communities in Europe or wherever. This is a touchy subject and I have always tried to be understanding of others’ restrictive views but I get frustrated that it’s all looked at in a black and white fashion. I’d better say a few things here before anyone reading this shuts me off and before I get back to the subject of maqams which is what I really wanted to write about.

Like language, music can be profane or sacred, and it springs from whatever the intention is. George Martin, erstwhile record producer of the Beatles, (who I briefly worked with in the 196os), is famous for saying there’s only good music and bad music. And I’m with him there 100%. Music has been a huge part of my life and I know it inside out from Thomas Tallis to Verdi by way of Tamla Mowtown and John Coltrane from Gilbert and Sullivan to British Folk Rock and Classical Andalusi Maghrebi music, both as performer, writer or audience. Forgive my pun but music underscores western civilisation, as it has my own life, in the sense that it gives you an emotional taste of a period of time that has gone and timelessness in the case of timeless music. And you can learn from that. But with mass commercialisation of music it is not what it was and in many ways I enjoy more and more silence and the sounds of nature as there is too much pointless music around, horribly amplified, unconnected to meaning or context. Music in cars, radios, TVs, ipods, supermarkets, planes, hotel foyers, ringtones – absolutely everywhere. Just too much. The real power of music is not now understood, having become another commodity to be exploited for a quick dollar. Much as I love music I’d be the first to warn of its dangers but also the first to advertise its huge benefits. But no reason to ban it. You would need an Inquisition to do that.

On the plus side music (singing included) can elevate the spirit, provide a release from stress and even be applied as a therapy for psychological and physical illnesses. Music therapy, was /is something specifically related to the maqamats and well known to the Ottomans and the Andalusians as it restored some kind of harmony, with the use of mainly instrumental music, to disturbed souls. Whilst maristans in both east and west were dedicated to this treatment in times past, it is now almost a forgotten science. Something well worth reviving. There is a quite a bit on the web relating to this subject and its revival in Turkey.

Dar-ül Kurr’a Madrasa, Erdine, Turkey. This hexagonal building was dedicated to music therapy as well as hydrotherapy in Ottoman times.

The maqamats exist in many musical cultures: in Egypt, Syria, Western China, Turkey, India and of course Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. They share much of the basic maqamat harmonic sequences and have very similar names but reflect the local musical traditions and to the uneducated ear can sound quite unrelated. I can’t claim to be an expert on this but am exploring this intuitively from what I do know from 40 years practical experience of Moroccan qasaid. I do know that Ziryab brought this musical science from Baghdad to Cordoba where he created the great Andalus maqamats blending Arab music from the Persian courts with Iberian music, Christian and even Jewish music of the peninsular. It left Spain for north Africa after the overthrow of Granada but only half of it is left extant passed down through families and now taught in conservatoires.

http://www.maqamworld.com/ is an interesting web site dedicated to explaining the modal system of arabic music. Worth a visit but it might be just a bit complicated for most people. And pity its interactive bits don’t work on a Mac. It’s pretty difficult for the western mind to wrap itself around the concepts involved on the site but it’s useful as a reference point.